WHEN THE CIVIL WAR REALLY ENDED

by David L. Geary

When news reached Washington, D.C., that the Civil War had ended, a crowd gathered at the White House. President Abraham Lincoln made a few remarks, then asked a band to play "Dixie." The healing began.

Yet the conflict went on, only differently. Memories haunted both sides. Northerners bragged victory. The South suffered under Reconstruction.

For many Americans the war really ended nearly fifty years after the last shot was fired with a poignant event which moved a nation. More than 54,000 Civil War veterans from both North and South, approaching the end of life, gathered on Pennsylvania's Gettysburg battlefield for one last time together.

These were the soldiers who fiercely fought each other at Bull Run, Antietam, Vicksburg, and hundreds of other battles and skirmishes. Now with white hair and slowness of step, they came from all over America to rejoin their old regiments and camp under the stars as they did fifty years before.

Most wore old uniforms and well-worn medals. Many came without an arm or a leg -- lost in long-ago combat. Nine veterans died surrounded by their comrades.

The idea for a Civil War veterans reunion at Gettysburg began in 1909 with Pennsylvania Gov. Edwin S. Stuart. With money from the state legislature, he appointed a "Fiftieth Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg Commission" to plan the event.

The Commission, made up of sixteen of the state's Civil War veterans, was chaired by J.M. Schoonmaker of Pittsburgh. The Commission wrote all state and territorial governors inviting them to make the reunion "worthy of its historical significance and an occasion creditable and impressive to our great and reunited Nation."

Response was overwhelming. Each state and territory, including Puerto Rico, Alaska, and Hawaii, pledged support. So did President William Howard Taft and Congress.

The plan quickly took shape. The reunion would be July 1-4, 1913, exactly fifty years after the Battle of Gettysburg. Speakers would include the President, Chief Justice, Vice President, Speaker of the House of Representatives, senators, congressmen, and governors. Pennsylvania would pay most of the costs, with some support from the federal government.

C. Irvine Walker of Charleston, S.C., former Confederate general and commander of United Confederate Veterans, told his members of receiving a first-hand invitation. "Your commander," he wrote them, "was met by his once enemies so cordially as to disarm prejudice, and made him feel that they were honestly desirous of commemorating a peace with which the soothing hand of time has blessed our country."

"May our gray heads rest in peace in those graves which will soon claim us, with the satisfaction that we have contributed to bringing to our country the blessings of peace and good will"

Reading Gen. Walker's letter, H.M. Trimble of Chicago, commander of the Northern veterans organization. Grand Army of the Republic, was deeply moved. He wrote Gen. Walker, "Let us assemble there, where so many comrades of the Blue and Gray found common sepulcher on that historic field. There, in that sacred presence, mutually pledge to each other our constant fealty to a reunited and indissoluble American Republic. With this invitation goes the outstretched hand of friendship."

The Confederate veterans read Mr. Trimble's letter at their 1912 convention in Macon, Ga. They passed a resolution hoping "this event may mark the final and complete reconciliation of the opposing armies of fifty years ago, and the permanent establishment of harmonious and fraternal relations between the North and South, and that it may gladden the hearts of all our countrymen."

Interest spread across the nation. In April 1913 the Commission mailed the long-awaited applications. The process was simple. Fill out a short form, prove veteran status, and return. For the first time, veterans caught a glimpse of what they'd experience.

Once at Gettysburg, it was all free. They would live much as they had done fifty years earlier -- in more than 6,500 tents on the old battlefield. Grouped by states, tents would hold eight veterans each. Each tent would have cots, blankets, two hand basins, water bucket, and two lanterns. Bugles would awaken and lull veterans to sleep. Meals would be served in mess tents. A large tent would hold 13,000 for ceremonies.

Families could attend, but were told the town of Gettysburg was small and they could not use the veterans-only camp. Most veterans decided to go alone.

Getting there was the problem. Many veterans couldn't afford the cost. Railroads responded with very low fares. Some states, like Michigan and Virginia, paid the way for their veterans. Private donations poured in. More than eighty percent of the veterans received free transportation.

Some went out of their way to help. Utah's governor gave his own money when his legislature failed to come through with funds. Ladies in Virginia provided their veterans new Confederate uniforms. Vermont gave its veterans cash, and said if any was left over to share it.

The Commission planned for 40,000 veterans, but reservations kept coming. In June the Commission needed help. Now nearly 55,000 veterans, average age 72, planned to attend. Boy Scouts from Washington, D.C., volunteered. The Red Cross set up rest stations throughout the battlefield. Pennsylvania mining companies contributed their medical teams. The U.S. Army scrambled to get more tents, lumber, food, ice for refrigeration, and other supplies to Gettysburg.

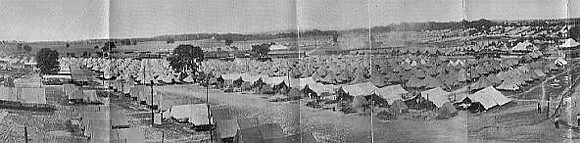

Finally, the big day came. The tent city had 50 miles of streets, 500 street lights, 122 telephones, a military band, its own post office and Western Union telegraph station, 32 bubbling ice water fountains, a police force, eight huge wash houses and latrines, and a fully-equipped hospital.

The Great Camp of 1913

More than 2,000 cooks in 173 kitchens and 425 Army field kitchens prepared to serve three-quarters of a million pounds of food in 688,000 meals.

The veterans, privates to generals, arrived from across the country and poured into 300 acres of tents. More than a hundred newspaper reporters and photographers began to send stories across the nation and around the world. As hundreds of special trains full of veterans carrying old battle flags, drums, and other keep-sakes arrived, a brightly shining sun carried temperatures well above 100 degrees.

Two veterans promptly collapsed from heat exhaustion and were hospitalized. One was an aged Union veteran from Philadelphia; the other, a Confederate veteran from Maryland. They recovered quickly, caught the spirit of the reunion, and became fast friends.

Promptly at 2 p.m. Chairman Schoonmaker rose to welcome the veterans. "It matters little to you or to me now, my comrades, what the causes were that provoked the War of the States in the sixties, but it matters, oh, so much that our heads were covered in the day of battle, that we were mercifully spared to join in this glorious reunion."

The veterans welcomed special guests, including Civil War nurses and children and grandchildren of famous generals.

State and unit reunions, ceremonies, dedications, concerts, speeches, parades, walking through the monument-laden battlefield, and visiting the spot where President Lincoln gave his famous address filled the veterans' days.

Conversation, song, and good-natured fun filled the cool nights. On the second evening Massachusetts veterans decided to "attack" the Confederates. A military band, playing loudly, led them towards the Confederate camp. Ohio and New Jersey quickly fell in.

When the column reached the Confederate camp, the Yankees found Virginia and Georgia veterans lined up on each side.

"Then came a scene that was indescribable," a reporter wrote. "The enemies of four years' bloody fighting wept like children. The lines were broken and the march was more of an old-fashioned Virginia love feast than a military pageant." Together they sang choruses of "Dixie" and "Yankee Doodle Dandy" into the night.

Emotions would run higher the next day.

On July 3, 1863, the Confederates at Gettysburg bravely hurled themselves across an open field against Union forces firing from behind a stone wall. The Confederates had no protection. The attack failed. Many died.

The assault had become one of the most famous in American military history. Pickett's Charge was a turning point of the Civil War.

On July 3, 1913, nine old, tottering Confederate survivors of that charge gathered in the open field. A slow walk turned into a slow run. To rousing cheers from onlookers, they hollered, waived hats, canes, and umbrellas.

When they reached the Stone Wall, they were met by the Union survivors who fifty years before had met them in bloody hand-to-hand combat. Photographers lowered their cameras out of respect. Some survivors clasped hands across the wall and cheered; others embraced their former foes and wept. They posed for pictures later.

That night, veterans enjoyed two hours of non-stop fireworks. More than 40,000 sightseers not connected with the reunion lined the roads around Gettysburg.

The next day, July 4, President Woodrow Wilson told the veterans, "We have found one another again as brothers and comrades...enemies no longer...our battles long past, the quarrel forgotten - - -except we shall not forget the splendid valor, the manly devotion of the men then arrayed against one another, now grasping hands and smiling into each other's eyes."

One aged Indiana veteran told a reporter why he came. He said his wife thought it might be too much for him. "It's going to mean something to all the younger generations to have us old fellows get together and show there isn't any hard feeling. It's a duty we owe the country, about the last we can fill, most of us, and I figured we ought to do it."

Americans and those in other lands read about the remarkable events in their newspapers. The Columbus, Ohio, Citizen reported, "Few days in American history have been so big as this. You may search the world's history in vain for such a spectacle."

The London Telegraph wrote, "It is impossible to spend a day in this tented city on the slopes of green pastures, where brave men fought and died so that the Republic might live, without proving that every American realizes that the North and South have trodden under their feet the bitter seeds of hate and anger, and in their place have upsprung the pure flowers of friendship, esteem, and affection."

The Atlanta Constitution observed, "The very idea of the Reunion itself, the merging of foe with friend on the field that was the Armageddon of the Civil War, has all the elements of drama on a huge scale. Better than all this is the thing for which it stands - - - the world's mightiest Republic purged of hate."

At noon on the last day, as sounds of church bells rolled across the old battlefield, buglers played the soldier's farewell. Everyone stopped. Flags fluttered to half-staff. Cannon boomed in the distance. And then for five minutes - - - before the raising of the flags and the sound of the National Anthem - - -that mighty brotherhood of 54,000 weathered veterans, some frail old men, stood silently at attention.

They had healed a nation. Their duty was done.

About the Author

Dr. David L. Geary, a native of Connellsville, Pa., is online professor of public relations at the University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. His ancestors served in both the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War.

Photosgraphs

(Photos are reproduced from Lt. Col. Lewis E. Beitler (editor), Fiftieth Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg: Report of the Pennsylvania Commission, Wm. Stanley Ray- State Printer, Harrisburg, 1914.)

Additional Resources

- The Great Reunion of 1913

- 1913 Gettysburg reunion - From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- Fiftieth Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg : report of the Pennsylvania Commission, presented to His Excellency, John K. Tener, Governor of Pennsylvania, for transmittal to the General Assembly (1913). This is the actual report and is available for reading online or download in various formats.

- The Great Reunion of 1913 - The Company of Military Historians

in pdf format - graphics intensive.

in pdf format - graphics intensive.